Navigating the Shifts. By Pat Farrell, OSF — LCWR President

Presidential Address, 2012 LCWR Assembly

The address that I am about to give is not the one I had imagined. After the lovely contemplative tone of last summer’s assembly, I had anticipated simply articulating from our contemporary religious life reflections some of the new things we sense that God has been doing. Well, indeed we have been sensing new things. The doctrinal assessment, however, is not what I had in mind!

Clearly, there has been a shift! Some larger movement in the Church, in the world, has landed on LCWR. We are in a time of crisis and that is a very hopeful place to be. As our main speaker, Barbara Marx Hubbard, has indicated, crisis precedes transformation. It would seem that an ecclesial and even cosmic transformation is trying to break through. In the doctrinal assessment we’ve been given an opportunity to help move it. We weren’t looking for this contoversy. Yet I don’t think that it is by accident that it found us. No, there is just too much synchronicity in events that have prepared us for it. The apostolic visitation galvanized the solidarity among us. Our contemplative group reflection has been ripenening our spiritual depth. The 50th anniversary of the Vatican II approaches. How significant for us who took it so to heart and have been so shaped by it! It makes us recognize with poignant clarity what a very different moment this is. I find my prayer these days often taking the form of lamentation. Yes, something has shifted! And now, here we are, in the eye of an ecclesial storm, with a spotlight shining on us and a microphone placed at our mouths. What invitation, what opportunity, what responsibility is ours in this? Our LCWR mission statement reminds us that our time is holy, our leadership is gift, and our challenges are blessings.

I think It would be a mistake to make too much of the docrinal assessment. We cannot allow it to consume an inordinate amount of our time and energy or to distract us from our mission. It is not the first time that a form of religious life has collided with the institutional Church. Nor will it be the last. We’ve seen an apostolic visitation, the Quinn Commission, a Vatican intervention of CLAR and of the Jesuits. Many of the foundresses and founders of our congregations struggled long for canonical approval of our institutes. Some were even silenced or ex-communicated. A few of them, as in the cases of Mary Ward and Mary McKillop, were later canonized. There is an inherent existential tension between the complementary roles of hierarchy and religious which is not likely to change. In an ideal ecclesial world, the different roles are held in creative tension, with mutual respect and appreciation, in an enviroment of open dialogue, for the building up of the whole Church. The doctrinal assessment suggests that we are not currently living in an ideal ecclesial world.

I also think it would be a mistake to make too little of the doctrinal assessment. The historical impact of this moment is clear to all of us. It is reflected in the care with which LCWR members have both responded and not responded, in an effort to speak with one voice. We have heard it in more private conversations with concerned priests and bishops. It is evident in the immense groundswell of support from our brother religious and from the laity. Clearly they share our concern at the intolerance of dissent even from those with informed consciences, the continued curtailing of the role of women. Here are selections from one of the many letters I have received: “I am writing to you because I am watching at this pivotal moment in our planet’s spiritual history. I believe that all the Catholic faithful must be enlisted in your efforts, and that this crisis be treated as the 21st century catalyst for open debate and a rush of fresh air through every stained glass window in the land.” Yes, much is at stake. Through it all, we can only go forward with truthfulness and integrity. Hopefully we can do so in a way that contributes to the good of religious life everywhere and to the healing of the fractured Church we so love. It is no simple thing. We walk a fine line. Gratefully, we walk it together.

In the context of Barbara Marx Hubbard’s presentation, it is easy to see this LCWR moment as a microcosm of a world in flux. It is nested within the very large and comprehensive paradigm shift of our day. The cosmic breaking down and breaking through we are experiencing gives us a broader context. Many institutions, traditions, and structures seem to be withering. Why? I believe the philosophical underpinnings of the way we’ve organized reality no longer hold. The human family is not served by individualism, patriarchy, a scarcity mentality, or competition. The world is outgrowing the dualistic constructs of superior/inferior, win/lose, good/bad, and domination/submission. Breaking through in their place are equality, communion, collaboration, synchronicity, expansiveness, abundance, wholeness, mutuality, intuitive knowing, and love. This shift, while painful, is good news! It heralds a hopeful future for our Church and our world. As a natural part of evolutionary advance, it in no way negates or undervalues what went before. Nor is there reason to be fearful of the cataclysmic movements of change swirling around us. We only need to recognize the movement, step into the flow, and be carried by it. Indeed, all creation is groaning in one great act of giving birth. The Spirit of God still hovers over the chaos. This familiar poem of Christopher Fry captures it:

”The human heart can go the length of God.

Cold and dark, it may be

But this is no winter now.

The frozen misery of centuries cracks, breaks, begins to move. The thunder is the thunder of the floes.

The thaw, the flood, the up-start spring. Thank God, our time is now

When wrong comes up to face us everywhere Never to leave until we take

The greatest stride of soul that people ever took

Affairs are now soul-size.

The enterprise is exploration into God…”

Christopher Fry – A Sleep of Strangers

I would like to suggest a few ways for us to navigate the large and small changes we are undergoing. God is calling to us from the future. I believe we are being readied for a fresh inbreaking of the Reign of God. What can prepare us for that? Perhaps there are answers within our own spiritual DNA. Tools that have served us through centuries of religious life are, I believe, still a compass to guide us now. Let us consider a few, one by one.

1.How can we navigate the shifts? Through contemplation.

How else can we go forward except from a place of deep prayer? Our vocations, our lives, begin and end in the desire for God. We have a lifetime of being lured into union with divine Mystery. That Presence is our truest home. The path of contemplation we’ve been on together is our surest way into the darkness of God’s leading. In situations of impasse, it is only prayerful spaciousness that allows what wants to emerge to manifest itself. We are at such an impasse now. Our collective wisdom needs to be gathered. It germinates in silence, as we saw during the six weeks following the issuing of the mandate from the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith. We wait for God to carve out a deeper knowing in us. With Jan Richardson we pray:

“You hollow us out, God, so that we may carry you, and you endlessly fill us only to be emptied again. Make smooth our inward spaces and sturdy, that we may hold you with less resistance and bear you with deeper grace.”

Here is one image of contemplation: 1 the prairie. The roots of prairie grass are extraordinarily deep. Prairie grass acutally enriches the land. It produced the fertile soil of the Great Plains. The deep roots aerate the soil and decompose into rich, productive earth. Interestingly, a healthy prairie needs to be burned regularly. 2 It needs the heat of the fire and the clearing away of the grass itself to bring the nutrients from the deep roots to the surface, supporting new growth. This burning reminds me of a similar image. There is a kind of Eucalyptus tree in Australia whose seeds cannot germinate without a forest fire. The intense heat cracks open the seed and allows it to grow. Perhaps with us, too, there are deep parts of ourselves activated only when more shallow layers are stripped away. We are pruned and purified in the dark night. In both contemplation and conflict we are mulched into fertility. As the burning of the prairie draws energy from the roots upward and outward, contemplation draws us toward fruitful action. It is the seedbed of a prophetic life. Through it, God shapes and strengthens us for what is needed now.

2.How can we navigate the shifts? With a prophetic voice

The vocation of religious life is prophetic and charismatic by nature, offering an alternate lifestyle to that of the dominant culture. The call of Vatican II, which we so conscientiously heeded, urged us to respond to the signs of our times. For fifty years women religious in the United States have been trying to do so, to be a prophetic voice. There is no guarantee, however, that simply by virtue of our vocation we can be prophetic. Prophecy is both God’s gift as well as the product of rigorous asceticism. Our rootedness in God needs to be deep enough and our read on reality clear enough for us to be a voice of conscience. It is usually easy to recognize the prophetic voice when it is authentic. It has the freshness and freedom of the Gospel: open, and favoring the disenfranchised. The prophetic voice dares the truth. We can often hear in it a questioning of established power, and an uncovering of human pain and unmet need. It challenges structures that exclude some and benefit others. The prophetic voice urges action and a choice for change.

Considering again the large and small shifts of our time, what would a prophetic response to the doctrinal assessment look like? I think it would be humble, but not submissive; rooted in a solid sense of ourselves, but not self- righteous; truthful, but gentle and absolutely fearless. It would ask probing questions. Are we being invited to some appropriate pruning, and would we open to it? Is this doctrinal assessment process an expression of concern or an attempt to control? Concern is based in love and invites unity. Control through fear and intimidation would be an abuse of power. Does the institutional legitimacy of canonical recognition empower us to live prophetically? Does it allow us the freedom to question with informed consciences? Does it really welcome feedback in a Church that claims to honor the sensus fidelium, the sense of the faithful? In the words of Bob Beck, “A social body without a mechanism for registering dissent is like a physical body that cannot feel pain. There is no way to get feedback that says that things are going wrong. Just as a social body that includes little more than dissent is as disruptive as a physical body that is in constant pain. Both need treatment.”

When I think of the prophetic voice of LCWR, specifically, I recall the statement on civil discourse from our 2011 assembly. In the context of the doctrinal assessment, it speaks to me now in a whole new way. St. Augustine expressed what is needed for civil discourse with these words: “Let us, on both sides, lay aside all arrogance. Let us not, on either side, claim that we have already discovered the truth. Let us seek it together as something which is known to neither of us. For then only may we seek it, lovingly and tranquilly, if there be no bold presumption that it is already discovered and possessed.”

In a similar vein, what would a prophetic response to the larger paradigm shifts of our time look like? I hope it would include both openness and critical thinking, while also inspiring hope. We can claim the future we desire and act from it now. To do this takes the discipline of choosing where to focus our attention. If our brains, as neuroscience now suggests, take whatever we focus on as an invitation to make it happen, then the images and visions we live with matter a great deal. So we need to actively engage our imaginations in shaping visions of the future. Nothing we do is insignificant. Even a very small conscious choice of courage or of conscience can contribute to the transformation of the whole. It might be, for instance, the decision to put energy into that which seems most authentic to us, and withdraw energy and involvement from that which doesn’t. This kind of intentionaltiy is what Joanna Macy calls active hope. It is both creative and prophetic. In this difficult, transitional time, the future is in need of our imagination and our hopefulness. In the words of the French poet Rostand:

“It is at night that it is important to believe in the light; one must force the dawn to be born by believing in it.”

3.How can we navigate the shifts? Through solidarity with the marginalized.

We cannot live prophetically without proximity to those who are vulnerable and marginalized. First of all, that is where we belong. Our mission is to give ourselves away in love, particularly to those in greatest need. This is who we are as women religious. But also, the vantage point of marginal people is a privileged place of encounter with God, whose preference is always for the outcast. There is important wisdom to be gleaned from those on the margins. Vulnerable human beings put us more in touch with the truth of our limited and messy human condition, marked as it is by fragility, incompleteness, and inevitable struggle.

The experience of God from that place is one of absolutely gratuitous mercy and empowering love. People on the margins who are less able to and less invested in keeping up appearances, often have an uncanny ability to name things as they are. Standing with them can help situate us in the truth and helps keep us honest. We need to see what they see in order to be prophetic voices for our world and Church, even as we struggle to balance our life on the periphery with fidelity to the center.

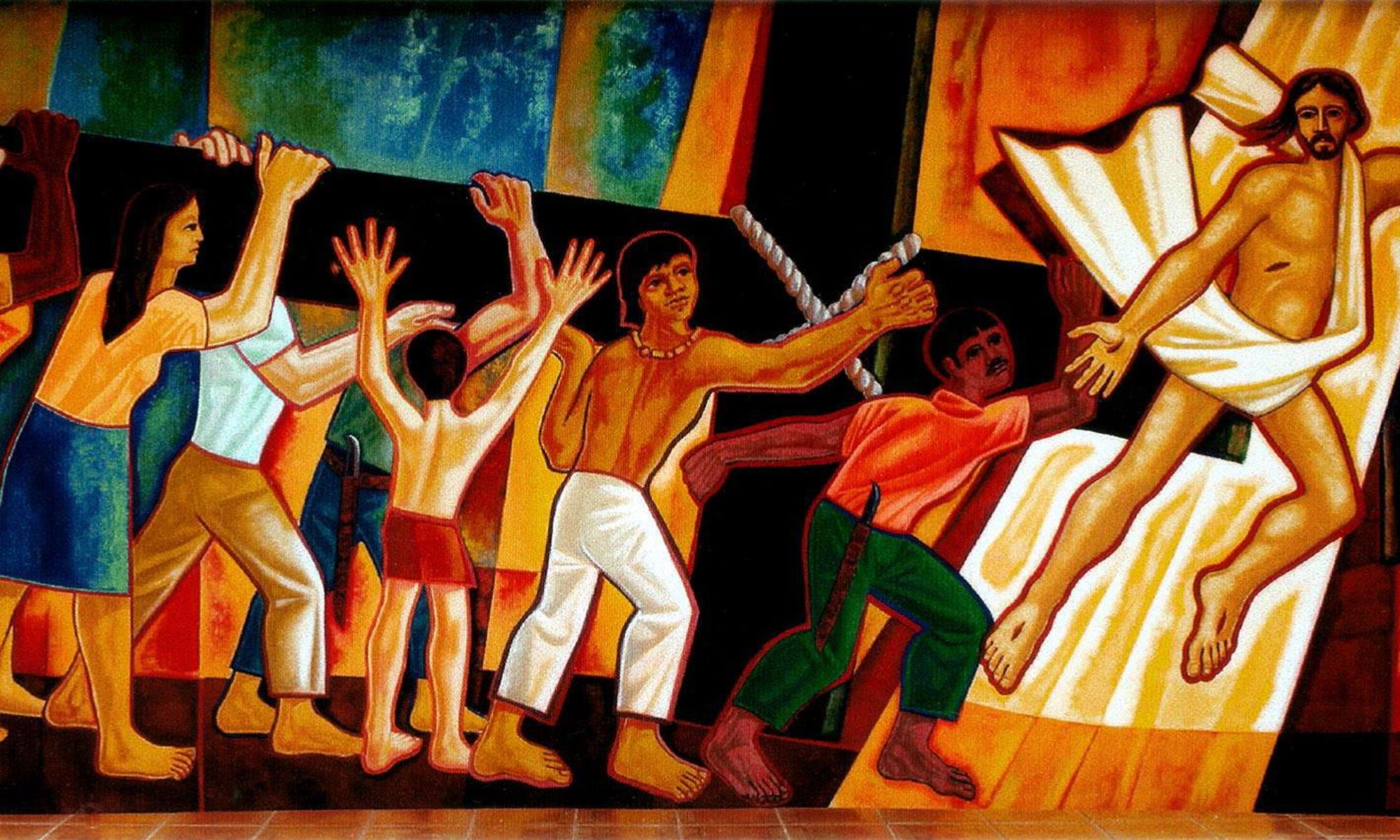

Collectively women religious have immense and varied experiences of ministry at the margins. Has it not been the privilege of our lives to stand with oppressed peoples? Have they not taught us what they have learned in order to survive: resiliency, creativity, solidarity, the energy of resistance, and joy? Those who live daily with loss can teach us how to grieve and how to let go. They also help us see when letting go is not enough. There are structures of injustice and exclusion that need to be unmasked and systematically removed. I offer this image of active dismantling. These pictures were taken in Suchitoto, El Salvador the day of celebration of the peace accords. 4 5 That morning, people came out of their homes with sledge hammers and began to knock down the bunkers, to dismantle the machinery of war. 6

4. How can we navigate the shifts? Through community

Religious have navigated many shifts over the years because we’ve done it together. We find such strength in each other! 7 In the last fifty years since Vatican II our way of living community has shifted dramatically. It has not been easy and continues to evolve, within the particular US challenge of creating community in an individualistic culture. Nonetheless, we have learned invaluable lessons.

We who are in positions of leadership are constantly challenged to honor a wide spectrum of opinions. We have learned a lot about creating community from diversity, and about celebrating differences. We have come to trust divergent opinions as powerful pathways to greater clarity. Our commitment to community compels us to do that, as together we seek the common good.

We have effectively moved from a hierarchically structured lifestyle in our congregations to a more horizontal model. It is quite amazing, considering the rigidity from which we evolved. The participative structures and collaborative leadership models we have developed have been empowering, lifegiving. These models may very well be the gift we now bring to the Church and the world.

From an evolved experience of community, our understanding of obedience has also changed. This is of particular importance to us as we discern a response to the doctrinal assessment. How have we come to understand what free and responsible obedience means? A response of integrity to the mandate needs to come out of our own understanding of creative fidelity. Dominican Judy Schaefer has beautifully articulated theological underpinnings of what she calls “obedience in community” or “attentive discipleship.” They reflect our post- Vatican II lived experience of communal discernment and decision making as a faithful form of obedience. She says: “Only when all participate actively in attentive listening can the community be assured that it has remained open and obedient to the fullness of God’s call and grace in each particular moment in history.” Isn’t that what we have been doing at this assembly? Community is another compass as we navigate our way forward. Our world has changed. I celebrate that with you through the poetic words of Alice Walker, from her book entitled Hard Times Require Furious Dancing:

The World Has Changed

The world has changed:

Wake up & smell

the possibility. The world

has changed: It did not change without

your prayers without

your determination to

believe

in liberation

&

kindness;

without

your

dancing

through the years that had

no

beat.

The world has changed: It did not

change

without

your numbers your fierce love

of self

& cosmos it did not change without

your strength.

The world has

changed:

Wake up!

Give yourself

the gift

of a new

day. 8

5. How can we navigate the shifts? Non-violently

The breaking down and breaking through of massive paradigm shift is a violent sort of process. It invites the inner strength of a non-violent response. Jesus is our model in this. His radical inclusivity incited serious consequences. He was violently rejected as a threat to the established order. Yet he defined no one as enemy and loved those who persecuted him. Even in the apparent defeat of crucifixion, Jesus was no victim. He stood before Pilate declaring his power to lay down his life, not to have it taken from him.

What, then, does non-violence look like for us? It is certainly not the passivity of the victim. It entails resisting rather than colluding with abusive power. It does mean, however, accepting suffering rather than passing it on. It refuses to shame, blame, threaten or demonize. In fact, non-violence requires that we befriend our own darkness and brokeness rather than projecting it onto another. This, in turn, connects us with our fundamental oneness with each other, even in conflict. Non-violence is creative. It refuses to accept ultimatums and dead-end definitions without imaginative attempts to reframe them. When needed, I trust we will name and resist harmful behavior, without retaliation. We can absorb a certain degree of negativity without drama or fanfare, choosing not to escalate or lash out in return. My hope is that at least some measure of violence can stop with us.

Here I offer the image of a lightning rod. 9 Lightning, the electrical charge generated by the clash of cold and warm air, is potentially destructive to whatever it strikes. 10 A lightning rod draws the charge to itself, channels and grounds it, providing protection. A lightning rod doesn’t hold onto the destructive energy but allows it to flow into the earth to be transformed. 11

6. How can we navigate the shifts? By living in joyful hope

Joyful hope is the hallmark of genuine discipleship. We look forward to a future full of hope, in the face of all evidence to the contrary. Hope makes us attentive to signs of the inbreaking of the Reign of God. Jesus describes that coming reign in the parable of the mustard seed.

Let us consider for a moment what we know about mustard. Though it can also be cultivated, mustard is an invasive plant, essentially a weed. 12 The image you see is a variety of mustard that grows in the Midwest. Some exegetes tell us that when Jesus talks about the tiny mustard seed growing into a tree so large that the birds of the air come and build their nest in it, he is probably joking. 13 To imagine birds building nests in the floppy little mustard plant is laughable. It is likely that Jesus’ real meaning is something like Look, don’t imagine that in following me you’re going to look like some lofty tree. Don’t expect to be Cedars of Lebanon or anything that looks like a large and respectable empire. But even the floppy little mustard plant can support life. Mustard, more often than not, is a weed. 14 Granted, it’s a beautiful and medicinal weed. Mustard is flavorful and has wonderful healing properties. 15 It can be harvested for healing, and its greatest value is in that. But mustard is usually a weed. 16 It crops up anywhere, without permission. And most notably of all, it is uncontainable. It spreads prolifically and can take over whole fields of cultivated crops. 17 You could even say that this little nuisance of a weed was illegal in the time of Jesus. There were laws about where to plant it in an effort to keep it under control.

Now, what does it say to us that Jesus uses this image to describe the Reign of God? Think about it. We can, indeed, live in joyful hope because there is no political or ecclesiastical herbicide that can wipe out the movement of God’s Spirit. Our hope is in the absolutely uncontainable power of God. We who pledge our lives to a radical following of Jesus can expect to be seen as pesty weeds that need to be fenced in. 18 If the weeds of God’s Reign are stomped out in one place they will crop up in another. I can hear, in that, the words of Archbishop Oscar Romero “If I am killed, I will arise in the Salvadoran people.”

And so, we live in joyful hope, willing to be weeds one and all. We stand in the power of the dying and rising of Jesus. I hold forever in my heart an expression of that from the days of the dictatorship in Chile: “Pueden aplastar algunas flores, pero no pueden detener la primavera.” “They can crush a few flowers but they can’t hold back the springtime.”

REFERENCES

Michael W. Blastic, OFM Conv., “Contemplation and Compassion: A Franciscan Ministerial Spirituality.”

Robert Beck, Homily: Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time, July 15, 2012. Mount St. Francis, Dubuque, Iowa

Judy Cannato, Field of Compassion: How the New Cosmology is Transforming Spiritual Life. Notre Dame, IN: Sorin Books, 2010.

Barbara Marx Hubbard, Conscious Evolution: Awakening the Power of Our Social Potential. Novato, CA: New World Library, 1998.

Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone, How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2012.

Jan Richardson, Night Visions: Searching the Shadows of Advent and Christmas. Wanton Gospeller Press, 2010.

Judith K. Schaefer, The Evolution of a Vow: Obedience as Decision Making in Communmion. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers

Margaret Silf, The Other Side of Chaos: Breaking Through When Life is Breaking Down. Chicago: Loyola Press, 2011.

Alice Walker, Hard Times Require Furious Dancing. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2010.

Fuente: www.lcwr.org

The Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR) is an association of the leaders of congregations of Catholic women religious in the United States. The conference has more than 1500 members, who represent more than 80 percent of the 57,000 women religious in the United States. Founded in 1956, the conference assists its members to collaboratively carry out their service of leadership to further the mission of the Gospel in today’s world.